Richland, Washington

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

Richland, Washington | |

|---|---|

| City of Richland | |

View over downtown Richland in 2018 | |

| Nickname(s): The Windy City, City Of the Bombers, Atomic City[1] | |

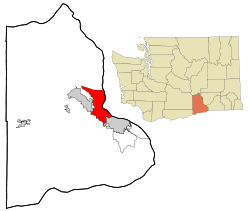

Location of Richland, Washington | |

| Coordinates: 46°16′47″N 119°17′33″W / 46.27972°N 119.29250°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Benton |

| Incorporated | April 28, 1910 |

| Re-incorporated | December 10, 1958 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager government |

| Area | |

• City | 42.62 sq mi (110.38 km2) |

| • Land | 39.22 sq mi (101.59 km2) |

| • Water | 3.39 sq mi (8.79 km2) |

| Elevation | 404 ft (123 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 60,560 |

• Estimate (2023)[3] | 63,757 |

| • Rank | US: 667th WA: 22nd |

| • Density | 1,345.5/sq mi (519.5/km2) |

| • Urban | 232,954 (US: 171st) |

| • Metro | 303,501 (US: 164th) |

| • CSA | 357,146 (US: 103rd) |

| • Tri-Cities | 215,024 |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP codes | 99352, 99353,99354 |

| Area code | 509 |

| FIPS code | 53-58235 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2410937[4] |

| Website | Ci.Richland.WA.US |

Richland (/ˈrɪtʃlənd/) is a city in Benton County, Washington, United States. It is located in southeastern Washington at the confluence of the Yakima and the Columbia Rivers. As of the 2020 census, the city's population was 60,560.[5] Along with the nearby cities of Pasco and Kennewick, Richland forms the Tri-Cities metropolitan area.

The townsite was established in 1905 and incorporated as Richland in 1910. The U.S. Army acquired the city and surrounding areas in 1943 for the establishment of the Hanford nuclear site, part of the Manhattan Project during World War II. Richland was transformed into a bedroom community for Hanford workers and grew to 25,000 residents by the end of the war. The city remained under control of Hanford contractors until it was re-incorporated as a city in 1958.

History

[edit]For centuries, the village of Chemna stood at the mouth of the current Yakima River. Today that village site is called Columbia Point. From this village, the indigenous Wanapum, Yakama and Walla Walla peoples harvested the salmon runs entering the Yakima River. Captain William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition visited the mouth of the Yakima River on October 17, 1805.[6]

Formative years

[edit]In 1904–1905, W.R. Amon and his son Howard purchased 2,300 acres (9 km2) and proposed a town site on the north bank of the Yakima River. Postal authorities approved the designation of this town site as Richland in 1905, naming it for Nelson Rich,[7] a state legislator and land developer. In 1906, the town was registered at the Benton County Courthouse. It was incorporated on April 28, 1910, as a fourth-class city.[citation needed]

Population growth in Richland accelerated following the opening of a permanent bridge over the Yakima River in 1907 and a highway to Kennewick in 1926. A cable ferry to Pasco operated across the Columbia River from 1894 to 1931, when it was replaced by a modern bridge.[6]

World War II

[edit]

Richland was a small farm town until the U.S. Army purchased 640 sq mi (1,660 km2) of land – half the size of Rhode Island – along the Columbia River during World War II for the Manhattan Project. On March 6, 1943, over 300 residents of Richland as well as those of the now vanished towns of White Bluffs and Hanford just upriver were evicted after a federal court order had condemned their properties for wartime use.[6]

The army transformed Richland into a bedroom community for the workers on its Manhattan Project facility at the nearby Hanford Engineering Works (now the Hanford site). The population increased from 300 in July and August 1943 to 25,000 by the end of World War II in August 1945. All land and buildings were owned by the government. Housing was assigned to residents, and token rent was collected; families were assigned to houses or duplexes; single people were placed in apartments or barracks. Everything necessary was provided, from free bus service to light bulbs, and trees were planted in people's yards by the government.[citation needed] Much of the city was planned by Spokane architect Gustav Albin Pherson and overseen by the Army Corps of Engineers. While there were dormitories and barracks built at the time, prefabricated duplexes and single-family homes are all that survive today.[6] Because homes were allocated based on family size and need, there were a number of floorplans available. These were each identified by a letter of the alphabet, and so came to be known as alphabet houses.[8]

Richland's link to the Army Engineers is suggested by its street nomenclature; many of the streets are named after famous engineers. The main street (George Washington Way) is named after the first president, who was a surveyor; Stevens Drive is named after John Frank Stevens, chief engineer of the Panama Canal and Stevens Pass; Goethals Drive is named after George W. Goethals, designer of the Panama Canal; and Thayer Drive is named after Sylvanus Thayer, superintendent of West Point and later founder of the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College. The rule is that if alphabet houses reside on a given street, they are named after an engineer or a type of tree.[citation needed]

Cold War era

[edit]With the end of the war, the Hanford workers' camp, originally located fifteen miles (24 km) north of Richland at the old Hanford town site, was closed down. Although many of the workers moved away as the war effort wound down, some of them moved to Richland, offsetting the depopulation that might otherwise have occurred.[citation needed] Management of the Hanford site and Richland itself was transferred to General Electric.[6]

Fears that the Soviet Union's intentions were aggressive set off the Cold War in 1947. The capacity to produce plutonium was increased beginning in 1947. When the Soviet Union developed and tested its first nuclear weapon in 1949, the U.S. nuclear program was reinvigorated. A second post-WWII expansion began in 1950 due to the war in Korea. Richland's Cold War construction boom resulted in Richland's population growing to 27,000 people by 1952. Many of these people lived in a construction camp of trailers located in what is now north Richland. With time, these trailers were vacated and the core city grew. Others lived at Camp Columbia near Horn Rapids until the camp was closed in 1950. In 2005 several dozen houses built in the northern part of the core city during this boom were added to the National Register of Historic Places as the Gold Coast Historic District.

Transition to private property

[edit]In 1954, Harold Orlando Monson was elected the first mayor of Richland and traveled to Washington, D.C., to negotiate increased rights (such as private home ownership) for citizens in military cities across the country.[citation needed] The U.S. Congress passed a law the following year to mandate the transfer of Richland and Oak Ridge to local control within five years, spurring a new incorporation attempt.[9] The federal government relinquished its land holdings in 1957 and sold the city's real estate to residents; the last home was sold on May 16, 1960.[10] Most of the people lived in duplexes; senior tenants were given the option to purchase the building; junior tenants were given the option to purchase lots in a newly platted area of north Richland.[citation needed]

Richland was re-incorporated as a chartered first-class city on December 10, 1958, five months after residents voted in favor of self-governance as a city.[9][11] Among the first additions to the new city was an expanded public library, which had been built by General Electric out of a Quonset hut.[12] As part of the transition, large areas of undeveloped land became city property. Richland's financial dependency on the federal Hanford facility changed little at this time because Hanford's mission as a weapons materials production site continued during the Cold War years.[citation needed]

After the production boom

[edit]

With the shutdown of the last production reactor in 1987, the area transitioned to environmental cleanup and technology. Now, many Richland residents are employed at the Hanford site in its environmental cleanup mission.[citation needed]

Richland High School's sports teams are called the Bombers, complete with a mushroom cloud logo. Some of the streets platted after 1958 are named after U.S. Army generals (such as Patton Street, MacArthur Street, Sherman Street, and Pershing Avenue) and after various nuclear themes (Einstein Avenue, Curie Street, Proton Lane, Log Lane, and Nuclear Lane). A local museum, the Reach Museum, tells the story of the cultural, natural, and scientific history of the Hanford Reach and Columbia Basin area; it replaced the now closed Columbia River Exhibition of History, Science, and Technology (CREHST) in 2014.[citation needed]

Washington State University, Tri-Cities was founded in northern Richland in 1989, growing out of a former Joint Graduate Center which had been affiliated with the University of Washington, Oregon State University, and Washington State University. Richland is also home to Kadlec Regional Medical Center. Columbia Basin College's Medical Training Center is near Kadlec Regional Medical Center.[citation needed]

Government

[edit]The city of Richland is a full-service city providing police services, fire protection, water utility services, solid waste services, electric utilities, parks and recreational facilities and services, maintenance of city streets and public facilities, and full library services featuring a state-of-the-art library operated by the city. The city pursues community and economic development and offers housing assistance.

The Richland Community Center is adjacent to Howard Amon Park, on the east side of the Columbia River. The building was designed by ARC Architects of Seattle, Washington. Many of its rooms have views of the park and Columbia River, which make it a venue for weddings and receptions, family reunions, birthday parties, business, and community meetings. The rooms are also used for a variety of general education and personal enrichment classes including courses in computer/technology, health & fitness, dance, arts & crafts, dog training, home & gardening, language lessons, and martial arts. The Community Center also serves as a gathering place for group recreation and gaming: cribbage, pinochle, bridge, pool, dominoes, and a host of other social activities are available to the public at large.

More recently, the Richland Community Center has hosted several important civic events including the Green Living Awards[13] and the Fall Carnival.[14]

As of 2016, the city was planning to rebuild its current city hall across Jadwin Avenue into the parking lot of the United States Federal Courthouse. This decision also includes moving the fire station, which is currently across George Washington Way, to the current site of city hall. The current city hall would be sold to eligible businesses.[15]

Police services

[edit]The City of Richland Police Department is composed of approximately 58 commissioned police officers and 15 support staff.[16]

Economy

[edit]Technology

[edit]After the end of World War II, Richland continued to be a center of production and research into nuclear energy and related technology.

It has been the home of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) since 1965. One of the two Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory sites is located immediately north of Richland. Numerous smaller high technology business and expert consultants have grown up around the Richland Technology Center as well.

Preferred Freezer Services Warehouse

[edit]Richland is home to the largest cold-storage facility on Earth—which is also one of the largest buildings on Earth by volume.

Major Employers

[edit]- Battelle Memorial Institute, operating PNNL

- Bechtel National Inc., building a waste vitrification plant

- Washington River Protection Solutions (a partnership of Amentum, Atkins, and Orano), controlling operations of the nuclear waste tank farms[17]

- Washington Closure Hanford (a partnership of AECOM, Bechtel, and CH2M Hill), providing waste management and cleanup efforts, including decontamination and demolition (D&D) of facilities along the Columbia River

- Hanford Mission Integrated Solutions (a partnership of Leidos, Centerra Group, and Parsons) providing infrastructure and sitewide services[18]

- Central Plateau Cleanup Company (a partnership of Amentum, Atkins, and Fluor), responsible for D&D of facilities on the site's Central Plateau[19]

- EnergySolutions, providing services to the U.S. government

- Energy Northwest, generating nuclear power at a nearby reactor facility

- Framatome creating nuclear fuel

- Lockheed Martin Services, Inc., providing technology services

- The U.S. Department of Energy, which operates the Hanford Site

Agriculture

[edit]Agriculture is important in the Richland area; the Tri-Cities area of the Columbia Basin grows excellent produce.[tone] Richland hosts an important food processor, Lamb Weston, which processes potatoes and other foods.

The production of wine in the lower Columbia Basin has become one of the area's main industries. Richland lies at the center of a viticulture area which produces internationally recognized wines in four major Washington appellations and serves as a center for wine tours.[citation needed] The Columbia Valley appellation which surrounds Richland contains over 7,000 hectares planted with wine grapes. On the west, the Yakima Valley appellation includes 5,000 hectares. To the east, the Walla Walla Valley appellation includes 500 hectares of wine grapes.

Business and industry

[edit]The Tri-City Industrial Development Council promotes both agricultural-related and technology-related industries in the region.

Top employers

[edit]According to Richland's 2021 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[20] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Battelle / Pacific Northwest National Laboratory | 4,500 |

| 2 | Kadlec Regional Medical Center | 3,532 |

| 3 | Bechtel National | 2,943 |

| 4 | Washington River Protection Solutions | 2,129 |

| 5 | Hanford Mission Integration Solutions[18] | 1,902 |

| 6 | Central Plateau Cleanup Company[19] | 1,682 |

| 7 | Richland School District | 1,500 |

| 8 | Energy Northwest | 1,100 |

| 9 | Lamb Weston | 750 |

| 10 | Framatome / Areva | 700 |

Education

[edit]The Richland School District serves the cities of Richland and West Richland with ten elementary schools, four middle schools, and three high schools.

Columbia Basin College, primarily located in Pasco, has a small branch campus in Richland.

Washington State University, Tri-Cities, established in North Richland in 1989, sits on the western bank of the Columbia River. The university offers undergraduate and graduate degree programs. It first admitted freshmen and sophomores in the fall of 2007.

Recreation

[edit]Golf

[edit]

There are three 18-hole golf courses and one 9-hole course in the area.[citation needed]

Outdoor activities

[edit]Richland has developed a number of parks, several of them fronting the Columbia and Yakima Rivers. The rivers provide boating, water skiing, fishing, kayaking and waterfowl hunting opportunities.[citation needed]

Richland is included in a bike trail system in the Tri-Cities which is named The Sacagawea Heritage Trail. The trail is a scenic river ride along the Columbia River through the Tri-Cities of Kennewick, Richland and Pasco. It is a 23-mile multipurpose blacktop loop trail on both sides of the river from Sacagawea State Park at the confluence of the Snake and Columbia Rivers up to the I-182 bridge at the Columbia Point Marina on the upper end. Three bridges join the trails on both sides, providing several ride options. There are numerous trailheads and access parking spots along the route.

Richland lies within a semi-arid, shrub-steppe environment, and has many interesting natural areas within or adjacent to the city:

- The Yakima River delta and wetlands lie within Richland and provide a habitat for many birds and animals. The area around the Yakima delta provides a wooded variation of the normal shrub steppe.

- The Badger Mountain Centennial Preserve protects Badger Mountain, located on the edge of Richland in the Richland GMA area. It provides views of the Tri-Cities and the Columbia and Yakima rivers. A non-profit group, Friends of Badger Mountain, worked to procure this shrub-steppe area that has the most native vegetation intact, and in 2005 built a trail to the summit. The 2-kilometer trail rises 300 meters above the trailhead in Richland.

- The Arid Lands Ecology Reserve, at the western edge of Richland on the Hanford Reservation, is the last remaining large block of undisturbed shrub-steppe habitat in the Pacific Northwest. The site has been closed to the public since the 1940s, preserving its character. It is managed as an environmental research area and wildlife reserve.

- North of Richland, the Hanford Reach, the last free-flowing stretch of the Columbia River in the U.S., provides sightseeing and salmon fishing. This free-flowing stretch flows through the Hanford Reach National Monument, which was created by Presidential proclamation in 2000 and is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Volunteers are working to construct an interpretive center on Richland's Columbia Point at the confluence of the Yakima and Columbia;[citation needed] in 2006, $22M of the necessary funds were in hand and construction was expected later that year.[needs update]

- The Amon Creek Natural Preserve in the south part of town protects wetlands around the creek and has several trails.

Sports

[edit]Sports teams in the immediate area include the Tri-City Americans WHL ice hockey team (which plays in Kennewick), and the Tri-City Dust Devils Single-A baseball team (affiliated with the Los Angeles Angels) which plays in Pasco.

Washington State University Tri-Cities has several club sports teams, including in rugby (2016 Northwest Cup Champions), volleyball, men's soccer and women's soccer.[21]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 39.11 square miles (101.29 km2), of which, 35.72 square miles (92.51 km2) is land and 3.39 square miles (8.78 km2) is water.[22] Elevation at the airport is 120 m (390 ft).

In the late 1970s, Richland sought to annex 5 square miles (13 km2) of unincorporated land in Franklin County on the east side of the Columbia River, anticipating development following the construction of Interstate 182. The move was blocked by Pasco, who had planned to annex much of the area themselves.[23] The Richland city government filed an appeal against the Franklin County Boundary Review Board in 1983 following their approval of Pasco's claim; the Washington Supreme Court affirmed the Franklin County decision.[24][25]

Richland Wye

[edit]

Richland Wye (46°14′12″N 119°13′59″W / 46.2368015°N 119.2330713°W) is an unincorporated community within the eastern city limits of Richland. It's also the location of the sole access bridge to Bateman Island over the Columbia River.

Climate

[edit]Richland receives about 7 inches (180 mm) of precipitation per year, giving it a semi-arid desert climate and resulting in a shrub-steppe environment. Summers are hot with infrequent thunderstorms, while winters are milder than all of Eastern Washington with snow falling only occasionally.[citation needed] During the 2021 Western North America heat wave, the maximum temperature of 118 °F (48 °C) was recorded in Richland which tied the previous all-time record high temperature in the state of Washington.[26] Nearby, the Hanford Site recorded a high of 120 °F (49 °C), the new state record.[27]

| Climate data for Richland, Washington, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1944–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

73 (23) |

82 (28) |

92 (33) |

105 (41) |

118 (48) |

113 (45) |

113 (45) |

106 (41) |

93 (34) |

78 (26) |

69 (21) |

118 (48) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 57.6 (14.2) |

60.4 (15.8) |

70.0 (21.1) |

79.9 (26.6) |

89.3 (31.8) |

95.2 (35.1) |

101.5 (38.6) |

99.9 (37.7) |

91.5 (33.1) |

78.6 (25.9) |

66.0 (18.9) |

58.2 (14.6) |

102.4 (39.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 40.6 (4.8) |

47.5 (8.6) |

57.1 (13.9) |

65.1 (18.4) |

73.9 (23.3) |

80.2 (26.8) |

89.3 (31.8) |

88.1 (31.2) |

78.9 (26.1) |

64.3 (17.9) |

49.0 (9.4) |

39.9 (4.4) |

64.5 (18.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 34.7 (1.5) |

38.8 (3.8) |

46.1 (7.8) |

53.0 (11.7) |

61.1 (16.2) |

67.3 (19.6) |

74.7 (23.7) |

73.6 (23.1) |

65.2 (18.4) |

53.0 (11.7) |

41.3 (5.2) |

34.1 (1.2) |

53.6 (12.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 28.8 (−1.8) |

30.1 (−1.1) |

35.1 (1.7) |

41.0 (5.0) |

48.3 (9.1) |

54.4 (12.4) |

60.0 (15.6) |

59.0 (15.0) |

51.4 (10.8) |

41.7 (5.4) |

33.6 (0.9) |

28.4 (−2.0) |

42.7 (5.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 13.0 (−10.6) |

16.8 (−8.4) |

24.3 (−4.3) |

30.7 (−0.7) |

37.5 (3.1) |

46.1 (7.8) |

52.0 (11.1) |

50.7 (10.4) |

40.9 (4.9) |

28.3 (−2.1) |

19.9 (−6.7) |

14.6 (−9.7) |

7.9 (−13.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −21 (−29) |

−22 (−30) |

7 (−14) |

23 (−5) |

30 (−1) |

38 (3) |

41 (5) |

39 (4) |

31 (−1) |

13 (−11) |

−6 (−21) |

−10 (−23) |

−22 (−30) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.04 (26) |

0.67 (17) |

0.64 (16) |

0.62 (16) |

0.63 (16) |

0.56 (14) |

0.23 (5.8) |

0.13 (3.3) |

0.29 (7.4) |

0.54 (14) |

0.87 (22) |

1.07 (27) |

7.29 (184.5) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.9 (4.8) |

1.9 (4.8) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

trace | 0.1 (0.25) |

2.3 (5.8) |

6.4 (16.16) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.8 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 4.7 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 6.7 | 10.3 | 11.9 | 83.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.9 | 5.0 |

| Source 1: NOAA (snow/snow days 1981–2010)[28][29] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[30] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 350 | — | |

| 1920 | 279 | −20.3% | |

| 1930 | 208 | −25.4% | |

| 1940 | 247 | 18.8% | |

| 1950 | 21,809 | 8,729.6% | |

| 1960 | 23,548 | 8.0% | |

| 1970 | 26,290 | 11.6% | |

| 1980 | 33,578 | 27.7% | |

| 1990 | 32,315 | −3.8% | |

| 2000 | 38,708 | 19.8% | |

| 2010 | 48,058 | 24.2% | |

| 2020 | 60,560 | 26.0% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 63,757 | [3] | 5.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] | |||

Based on per capita income, one of the more reliable measures of affluence, Richland ranks 83rd of 522 areas ranked in the state of Washington—the highest rank achieved in Benton County.

2010 census

[edit]As of the 2010 census,[32] there were 48,058 people, 19,707 households, and 12,974 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,345.4 inhabitants per square mile (519.5/km2). There were 20,876 housing units at an average density of 584.4 per square mile (225.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 87.0% White, 1.4% African American, 0.8% Native American, 4.7% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 2.7% from other races, and 3.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 7.8% of the population.

There were 19,707 households, of which 31.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.6% were married couples living together, 10.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.2% had a male householder with no wife present, and 34.2% were non-families. 28.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 2.97.

The median age in the city was 39.4 years. 24.2% of residents were under the age of 18; 8.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 24.7% were from 25 to 44; 28.4% were from 45 to 64; and 14.6% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 49.0% male and 51.0% female.

2000 census

[edit]As of the 2000 census, there were 38,708 people, 15,549 households, and 10,682 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,111.8 people per square mile (429.3 people/km2). There were 16,458 housing units at an average density of 472.7 per square mile (182.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 89.55% White, 1.37% African American, 0.76% Native American, 4.06% Asian, 0.11% Pacific Islander, 1.85% from other races, and 2.31% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 4.72% of the population.

There were 15,549 households, out of which 34.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56% were married couples living together, 9.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.3% were non-families. 27.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.48 and the average family size was 3.02.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 27.2% under the age of 18, 7.5% from 18 to 24, 27.1% from 25 to 44, 25.4% from 45 to 64, and 12.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 96 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $53,092, and the median income for a family was $82,354 (Money CNN). Males had a median income of $52,648 versus $30,472 for females. The per capita income for the city was $25,494. About 5.7% of families and 8.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 10.8% of those under age 18 and 5.6% of those age 65 or over.

Transportation

[edit]Richland is served by Richland Airport, located in the city, as well as the Tri-Cities Airport, located in nearby Pasco. Both have only domestic flights. Also in Pasco is an Amtrak station, where the Portland-Chicago Empire Builder makes a stop.

Ben Franklin Transit provides bus transportation within Richland and the Tri-Cities area.

Interstate 82 runs to the west of the city and connects to Yakima, Washington and Interstate 90, to the north, and Hermiston, Oregon and Interstate 84, to the south. Interstate 182 provides the primary east-west connection among the Tri-cities, Richland, Kennewick, and Pasco.

Notable people

[edit]- James (Jim) F. Albaugh – Executive Vice President, The Boeing Company

- Stu Barnes – NHL former player and coach; an owner of the Tri-City Americans

- Kayla Barron – NASA astronaut[33]

- Beefy – nerdcore artist; real name Keith A. Moore

- Tyler Brayton – National Football League for the Carolina Panthers

- Travis Buck – San Diego Padres outfielder

- Orson Scott Card – science fiction writer; born in Richland

- Gene Conley – Major League Basketball and Baseball player, RHS

- Larry Coryell – jazz guitarist, RHS class of 1961

- Westley Allan Dodd – serial killer and child molester

- Santino Fontana – Broadway and film actor[34]

- Liz Heaston – first female to score points in a college football game

- Ty Jones – former NHL player and first round pick in the 1997 NHL draft

- Kurt Kafentzis – former NFL defensive back

- Mark Kafentzis – former NFL defensive back

- Olaf Kölzig – retired NHL goaltender; owner of the Tri-City Americans

- James N. Mattis – United States Secretary of Defense; General, U.S. Marine Corps[35]

- Mike McCormack – U.S. Representative from the Fourth Congressional District

- Jimmy McLarnin – Irish boxer[36]

- Nate Mendel – Sunny Day Real Estate and Foo Fighters bassist

- Michael Peterson – Country western singer

- Jason Repko – Major League Baseball outfielder

- Kathryn Ruemmler – White House Counsel to President Barack Obama

- Leon Rice – Basketball coach[37]

- Hope Solo – United States women's national soccer team goalkeeper

- Sharon Tate – actress; Miss Richland, 1959

- John Archibald Wheeler – theoretical physicist

- Rachel Willis-Sørensen – American operatic soprano

Sister city

[edit]Richland's sister city is:[38]

Hsinchu, Taiwan

Hsinchu, Taiwan

See also

[edit]- Hanford High School

- Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

- Hanford Site

- Washington State University, Tri-Cities

- Ben Franklin Transit

- Kate Brown

References

[edit]- ^ "Kiwanis Club of Atomic City, Richland, Washington". Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places of 20,000 or More, Ranked by July 1, 2023 Population: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023". United States Census Bureau. May 2024. Retrieved December 23, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Richland, Washington

- ^ "QuickFacts Richland City, Washington".

- ^ a b c d e Kershner, Jim (January 8, 2008). "Richland — Thumbnail History". HistoryLink. Retrieved October 23, 2024.

- ^ Meany, Edmond S. (1923). Origin of Washington geographic names. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 244.

- ^ "Home Blown: The History of the Homes of Richland". City of Richland. Archived from the original (pdf) on July 18, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ^ a b Kershner, Jim (January 8, 2008). "Richland votes to incorporate as a first-class city, thus making the transition from being federally owned to being a self-governing city, on July 15, 1958". HistoryLink. Retrieved October 23, 2024.

- ^ "All A-City Homes Are Sold". Tri-City Herald. December 11, 1960. p. 8. Retrieved October 23, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Cool Air Cuts Crowd For Charter Affair". Tri-City Herald. December 14, 1958. p. 1. Retrieved October 23, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Richland Gets Quonset Hut Library Site". Spokane Daily Chronicle. December 13, 1958. p. 3. Retrieved October 23, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Green Living Awards". Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- ^ Herald, Tri-City (September 28, 2013). "Community Center to Hold Green". Tri-City Heral. Archived from the original on August 9, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- ^ City website, Richland (April 4, 2016). "Swift Corridor and Future City Hall". Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ Schilling, Sara; Herald, Tri-City. "Richland Police Department honors officers".

- ^ Cary, Annette (April 26, 2022). "Elite Construction, Pasco, WA, wins Hanford site contract". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Cary, Annette (November 5, 2021). "MSA earns $14M in incentive pay for final months at Hanford". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Cary, Annette (October 27, 2020). "Feds allow more time for $16 billion in new contracts at Hanford to take effect". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ City of Richland Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2021 (Report). City of Richland. August 25, 2022. p. 212. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ "WSU Tri-Cities | Campus Recreation". Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ Metcalf, Gale (August 13, 1980). "Pasco, Richland tangle on Franklin annexation". Tri-City Herald. p. 1.

- ^ "Court upholds Pasco in annexation battle with Richland". Tri-City Herald. Associated Press. January 26, 1984. p. B1.

- ^ Richland v. Boundary Review Board, 100 Wn.2d 864 (Washington Supreme Court January 26, 1984).

- ^ Cary, Annette (July 9, 2021). "Hottest day ever near Tri-Cities. It's just one of many records smashed in heat wave". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ "Records". National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Richland, WA (1991–2020)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Richland, WA (1981–2010)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Pendleton". National Weather Service. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ Garcia, Mark (February 7, 2018). "Astronaut Candidate Kayla Barron". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on June 24, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ Sullivan, Lindsey. "Tootsie Star Santino Fontana Wins First Tony Award". Broadway.com. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ^ Culverwell, Wendy (October 25, 2019). "Mattis could receive Congressional Gold Medal under Newhouse proposal". Yakima Herald-Republic. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ Jimmy McLarnin, Top Boxer Called Baby Face, Dies at 96

- ^ Morrow, Jeff (December 16, 2020). "Tri-Cities native earns 200th victory. And credits his Richland Bomber roots". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ "Sister cities". hccg.gov.tw. Hsinchu City. January 22, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Kate Brown, Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Elizabeth Gibson, "Images of America: Richland," Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2002.

- Barbara J. Kubik, Richland, Celebrating Its Heritage. Richland, WA: City of Richland, Washington, 1994.

- Paul Loeb, Nuclear Culture: Living & Working in the World's Largest Atomic Complex. Philadelphia, PA: New Society Publishers, 1986.

- Christine F. Noonan, Federal City Revisited: Atomic Energy and Community Identify in Richland, Washington. PhD dissertation. Ball State University, 2000.

- S.L. Sanger, Hanford and the Bomb: An Oral History of World War II. Seattle, WA: Living History Press, 1989.

External links

[edit]- Richland, Washington

- Tri-Cities, Washington

- 1905 establishments in Washington (state)

- Cities in Benton County, Washington

- Cities in Washington (state)

- Manhattan Project sites

- World War II Heritage Cities

- Populated places established in 1905

- Washington (state) populated places on the Columbia River

- Populated places on the Yakima River